Wine History in Anatolia

“Neolithic Period”

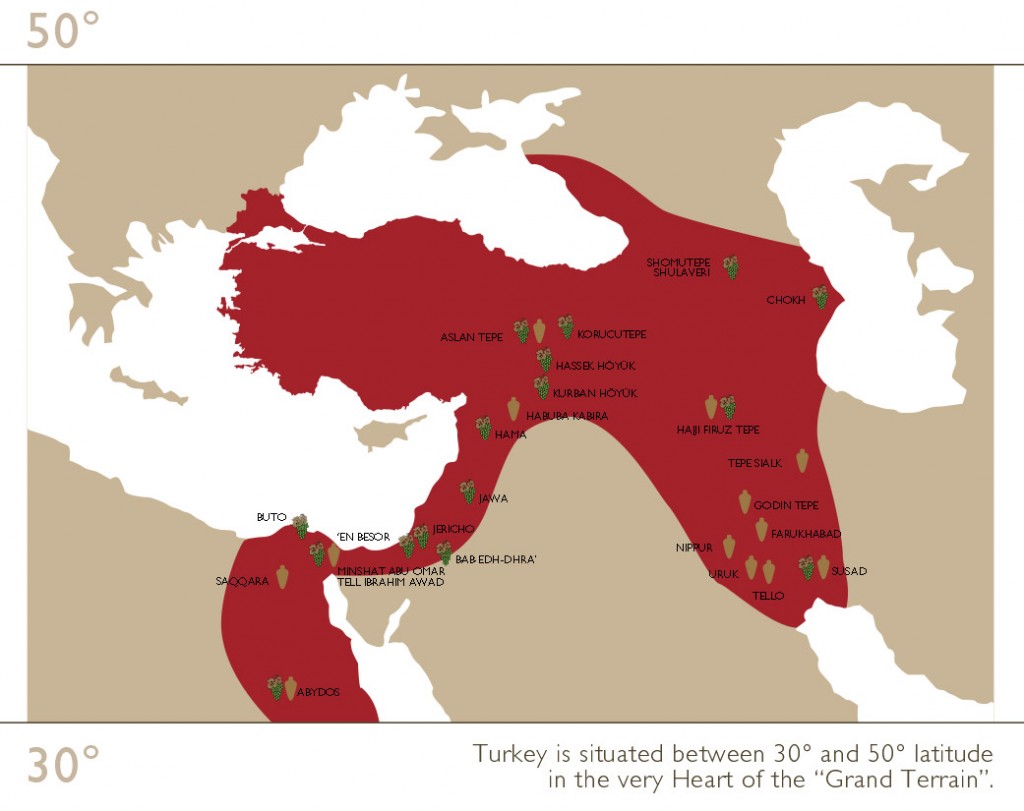

Vitis Vinifera’s Natural Distribution and Archaeological Discoveries.

According to archeobotanists, grape was reclaimed in East Anatolia, Georgia and Armenia trio.

Vitis Vinifera grows in a band with 6000 km long from Middle East to Spain and 1300 km wide from Crimean to West Africa.

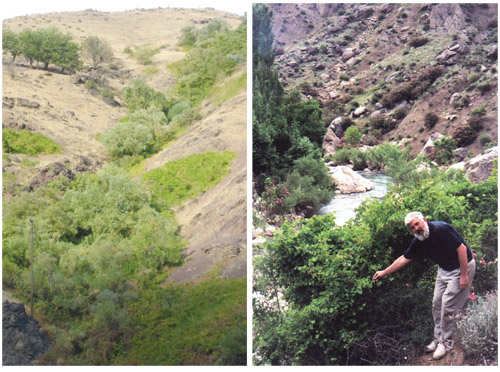

Primal Vinifera in Eastern Anatolia

Dr. Patrick McGovern Collecting

Wild Grapevines (at the Headwaters of the Tigris River)

Wine History in Anatolia from Bronze Age to Antiquity

The first traces of viticulture and winemaking in Anatolia date back 7,000 years. Wine had an indispensable role in the social lives of the oldest civilizations of Anatolia the Hattis and the Hittites. It was the primary libation offered to the gods during rituals attended by royalty and high governors. Provisions protecting viticulture in Hittite law, and the custom of celebrating each vintage with a holiday, suggest that wine was important to both ancient economies and ancient cultural practices.

The Phrygians introduced wine to Greek colonists on Anatolia’s western flank

The Phrygians introduced wine to Greek colonists on Anatolia’s western flank

For the Phrygians, who lived in Anatolia after the Hittites, wine was an essential part of daily life and an important lement in their diet along with olive oil, fish, and bread. The Phrygians introduced wine to Greek colonists on Anatolia’s western flank, and by the 6th century BC wine was being exported as far as France and Italy from trading and production entres such as Tabae (Tavas, near the present-day Pamukkale) and Klazomenai (near Urla) both in the southern Aegean region and Ainos (Enez) to the north. Knidos (today’s Datça), on the southwest Mediterranean coast, and the island of hodes were also leading centres for the wine trade. One of these early Anatolian grapes, Misket, became known as uscat in Europe. Another variety from Smyrna (today’s Izmir), was used in the production of the famous wine of Pramnios, which is mentioned in Homer’s Iliad.

Wine History in Anatolia “Hellenistic Period Wine Regions”

İzmir

“Pramneion, produced in ‹zmir Region was a dry and full bodied wine with high tannin and alcohol.”

Illias Odysseia

Gallipoli

“Phonecia colony Lampsakos(Lapseki) is known with its wines.”

Strabo, Geografia

Central Anatolia

In Galatia Region in Central Anatolia, sweet wine was produced called Scybelites.

“Scybelites produced in Galatia always keeps its freshness as the Halyntium wine of Sicily.”

Gaius Plinius Secundus

Wine History in Anatolia “from Ottomans to Turkish Republic”

Later still, Turkish tribes arrived in Anatolia from Central Asia they, too, drank wine. Productioncontinued even after Islam began to dominate the region, and a comfortable balance developed between Christian and Muslim residents: Christians, for the most part, produced the wine; both Christians and Muslims consumed it. During the long period of the Ottoman Empire (1299–1923), wine production and trade were carried out exclusively by non-Muslim minorities (Greeks, Armenians, Syrians, and others). However, what we today would call wine-bars, usually in Christian eighborhoods, were also patronized by Muslims. During the Ottoman period, the general atmosphere of tolerance was interrupted from time to time by official prohibitions on the use and sale of alcohol. Wine-bars were forced to close and heavy sanctions, even death penalties, were applied to those who didn’t obey the new rules. The prohibitions were always short-lived, however each time they would be first loosened, then eventually lifted completely. This regular reversal of policy had an economic reason: the tax collected from wine sales was an important source of income for the Ottoman treasury, so any long-term banning of alcohol sales contradicted state interests. Even during periods of prohibition, vineyards were never uprooted: grape production was simply diverted to other types of consumption. A ready supply of grapes enabled wine production to recover rapidly after each hiatus.

Wine production reached record levels and alcohol prohibitions ceased during the second half of the 19th century, in the atmosphere of tolerance and freedom brought about by the Ottoman modernization movement. At the same time European vineyards were being devastated by an epidemic of phylloxera (a vine-attacking insect), reducing wine production dramatically. In order to meet the resulting surge in European demand, the Ottoman Empire’s wine exports increased substantially reaching 340 million litres in 1904.

Wine History in Anatolia

“From the Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic”

Later still, Turkish tribes arrived in Anatolia from Central Asia and they, too, drank wine. Production continued even after Islam began to dominate the region, and a comfortable balance developed between Christian and Muslim residents: Christians, for the most part, produced the wine; both Christians and Muslims consumed it. During the long period of the Ottoman Empire (1299–1923), wine production and trade were carried out exclusively by non-Muslim minorities (Greeks, Armenians, Syrians, and others). However, what we today would call wine-bars, usually in Christian neighborhoods, were also patronized by Muslims.

During the Ottoman period, the general atmosphere of tolerance was interrupted from time to time by official prohibitions on the use and sale of alcohol. Wine-bars were forced to close and heavy sanctions, even death penalties, were applied to those who didn’t obey the new rules. The prohibitions were always short-lived, however each time they would be first loosened, then eventually lifted completely. This regular reversal of policy had an economic reason: the tax collected from wine sales was an important source of income for the Ottoman treasury, so any long-term banning of alcohol sales contradicted state interests. Even during periods of prohibition, vineyards were never uprooted: grape production was simply diverted to other types of consumption. A ready supply of grapes enabled wine production to recover rapidly after each hiatus.

Wine production reached record levels and alcohol prohibitions ceased during the second half of the 19th century, in the atmosphere of tolerance and freedom brought about by the Ottoman modernization movement. At the same time European vineyards were being devastated by an epidemic of phylloxera (a vine-attacking insect), reducing wine production dramatically. In order to meet the resulting surge in European demand, the Ottoman Empire’s wine exports increased substantially reaching 340 million litres in 1904.

“The Turkish Republic”

There was a considerable amount of wine production before World War I and the War of Independence in Turkey. But wars affected production negatively, especially in the Thrace and Aegean regions.

The production of all alcoholic beverages went under the control of government monopoly in 1927, with the exception of wine, for which private production and the development of vineyards was still permitted. This was specifically done to develop and protect wine production. The only restriction, which in today’s terms could be called “controlled wine regions-appellation controllée”, was the permissions given to wine production on specific regions where wine grapes were being produced. In 1928 the government began to support wine producers with technical knowhow and semi-financial support. (There was also support for export tax exemptions and a support fee/kg).

M.Emile Bouffart was one of the first pioneering consultants who evaluated wines and the wine regions in Turkey, including advising on where to develop wineries.

In 1946 there were 28 small sized wineries all around Turkey exploring the potential quality of wine production with different varieties and terroirs under the Government Monopoly.

Marcel Biron was also one of the consultants working for the Government Monopoly and identifying different wine regions and wines in Turkey (1937-1947).

The 1950’s government initiated French grape varieties for plantation in the Aegean and Thrace regions (Semillon, Clairette, Sylvaner, Gamay, Cinsaut, Pinot Noir and Cabernet Sauvignon are among the varieties planted and explored during these dates).

The subsequent decrease in quality began with the non-implementation of this “controlled wine regions” regulation as well as political changes in the 1960’s. Private producers stayed in the market throughout this period, but remained relatively small in size.

By the late 1980s, as the Turkish economy began to integrate with other global economies and deregulation became more prevalent, the tourism sector also began to develop, thus substantially boosting wine sales. This was the impetus for the wineries to invest in the latest technology, machineries, to develop their wineries, begin investment in their vineyards and plant international and local grape varieties to international quality standards